Biblical Paradigms Amongst Scholars

New Discoveries Challenge Paradigms

Over the past dig season, a number of paradigm-shifting discoveries were made that challenge traditional thinking. The result has been an acknowledgement that the way history books are written will now change. In some cases, clear bias has been exposed, particularly of the political or anti-religious varieties. Established schools of thought and models of history in the Levant are shifting. 2019 has been a dramatic year for archaeology in the land of Israel, and our Thinkers have had a front row seat to the drama.

Naturally, though, readers may have questions about how to think through these issues for themselves. Questions for reflection include: “Why are there sometimes such strong differences of interpretation and opinion among established experts?” Others may wonder, “When differences show up, how can I know who to trust?” Additional questions may be: “How do paradigms develop and become established?” or “What tools can I use to identify faulty thinking?”

So, to close out 2019 and usher in 2020, we’re dedicating a Thinker series to equipping our readers to critically evaluate claims and new findings on their own. Our hope is that by the end, we will all have some sharper tools that we can use to do our own kind of excavation – the unearthing of biases and prejudices.

To begin our series, let’s start with a word from one of the greatest legal and literary minds of all time.

From Law-giver to Lyricist

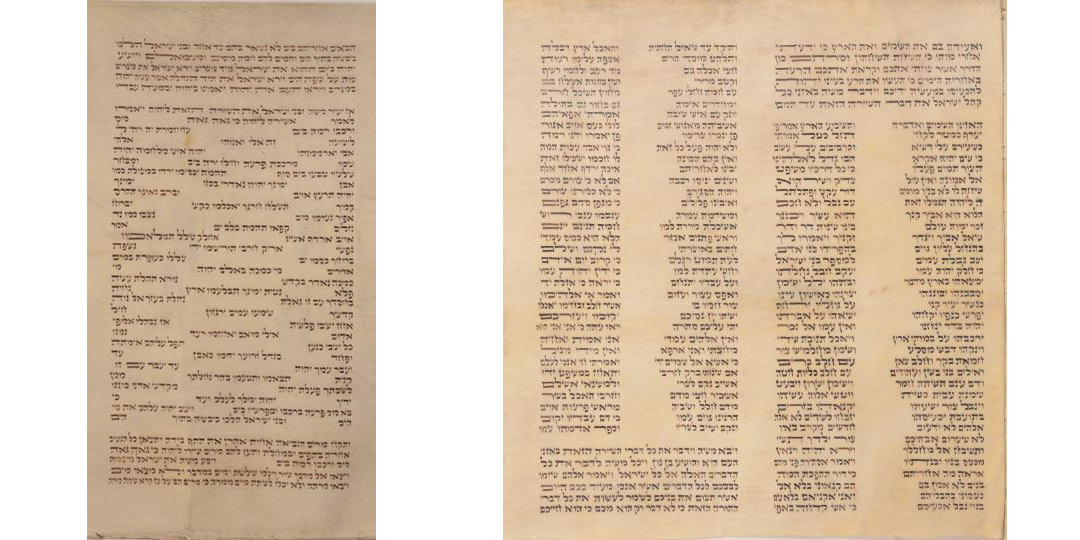

Moses is known as the great prophet and law-giver. However, some of the greatest lyrics in the world also come to us from the hand Moses. Most readers will likely think of the song in Exodus 15, known as The Song of the Sea. For others, perhaps, the concluding song in Deuteronomy 32 known as The Song of Moses comes to mind. These have long been enjoyed by worshippers and are visually identifiable in Hebrew scrolls by their distinctive formatting.

(Photo Credit: MIKRA Research Laboratory)

Other readers may think of the many examples of verse and poetic expression scattered throughout the narrative sections of the Torah. These delightful gems are in virtually every column of Hebrew text throughout the Pentateuch and are thrilling to discover. Examples include the kind of literary artistry described in our previous article on literary genius in the creation account.

However, there is another song, or more precisely, a prayer attributed to Moses that is particularly compelling at this time of year. Psalm 90, identified as “A Prayer of Moses, the man of God,” is the first psalm in Book 4 of the Book of Psalms. The superscription (the introduction written at the head of the psalm) identifies its author as Moses, an attribution that makes it the earliest of the psalms, chronologically speaking. This means that the Israelites could have been meditating on the message of this Mosaic hymn long before David or the Psalter ever came into existence.

In this psalm, Moses presents his readers with a call to personal reflection. Its spirit promotes awareness of the brevity of life, humility, and thoughtful living as finite creatures beneath the gaze of a sovereign Creator. It would be easy to imagine the prayer being used devotionally, or in worship by Israelites during the long years of the wilderness wanderings. Moses teaches us, though, that the goal is not simply to be reflective, but to gain wisdom in reflection. In verse 12, he prays, “So teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.” Certainly an appropriate attitude to close out this year.

The context of this passage is so poignant, that it is employed by Peter in the New Testament as a reminder that a day of reckoning is coming (2 Peter 3:8). Along with Moses, we recognize the brevity of life, the passing of days, and the importance of reflecting over life in yearly cycles. So, in keeping with the Mosaic hymn, as we near the end of 2019, we recall Psalm 90:12 and join with Moses in pursuing a heart of wisdom.

Presuppositions and Critical Theories

It may come as a surprise for some to learn, though, that modern critics often dismiss the idea of Mosaic authorship of the psalm. In fact, the authorship, unity, and theological purpose (as traditionally understood) of many of the psalms are called into question. These kinds of approaches tend to be connected to a critical interpretive approach based on the same kinds of presuppositions held by minimalists in the field of archaeology. Minimalists are those who assign limited validity to the historical accounts found in the Bible while maximalists assign a great deal of weight to the biblical account.

Just as conservative archaeologists are sometimes marginalized, those who take seriously the superscriptions of the Psalms, or hold to traditional views of authorship for the rest of Scripture, may be pejoratively dismissed as “restricted by an authorship dogma.” (See Leopold Sabourin, The Psalms: Their Origin and Meaning New York: Alba House, 1970, p. 37.)

Archaeological Evidence Reveals Weakness in Minimalist Approach

Over the past dig season, a number of important archaeological discoveries were made that have shifted the landscape, so to speak. The research that has flowed from those involved with the findings, and secondary analysis of the research, has produced new thinking that has soundly challenged established paradigms. These are exciting, in part because challenging traditional thought is one of the most energizing kinds of endeavors. More importantly, though, these discoveries have served to verify the biblical record in several places, have revealed deficiencies in minimalist approaches, and have advanced Scripture as an objective source of reliable history.

This naturally raises questions, though. For example, “Why are there sometimes such strong differences of interpretation and opinion among established experts?” Others may wonder, “When differences show up, how can I know who to trust?” Additional questions may include: “How do paradigms develop and become established?” or “What tools can I use to identify weak, biased, or faulty thinking?” These are the kinds of questions that deserve careful consideration.

Just as with biblical interpreters, when archaeologists make discoveries, those discoveries must be interpreted. As those interpretations are processed, they become part of a narrative. As that narrative is supported, it becomes the consensus and shapes our view of the past. The best scholars try to give a straightforward account of the evidence. However, interpretation of archaeological evidence is impacted by things such as differences in individual backgrounds, political viewpoints, personal experiences, philosophical outlook, and more.

In the world of archaeology, this shows up most dramatically in the differences between minimalists and maximalists. This means that the worldview of the archaeologist plays a huge factor in the interpretation of evidence.

It can also drive questions like, “Where are we going to dig, and what can we expect to find?” It may result in individual archaeologists, or teams of archaeologists looking for different things. The way the worldview of the individual impacts methodology, interpretation, and decision making may include factors about which the individual is not even aware.

For example, in the recent article on the discovery matching the biblical altar at the Shiloh Archaeological Park, notice how Scott Stripling explained how he and Israel Finkelstein made different observations by looking at the same collection of bones. Finkelstein observed the bones, and concluded that they were from Canaanite ritual sacrifice. Looking at the same bones, Stripling more closely observed that these were bones mostly from the right side of the animal, and from kosher animals at that.

Stripling made observations that had previously been missed, interpreted them differently, and drew different conclusions. In this case, Stripling rightly noted that the bones were consistent with priestly sacrifices as described in the Torah. This supported the narrative that Shiloh was, in fact, an ancient location of Israelite worship.

Recall how in the recent story about the Canaanite metropolis at En Esur, Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist and excavation co-director Dina Shalem stated, “Even in our wildest imaginings, we didn’t believe we would find a city from this time in history.” The discovery was so far beyond the pale, that no one had even considered looking. This archaeological discovery was made by accident.

Had it not been for the Israeli policy of excavation before building, the city may have never been found. Instead, excavation director Yitzhak Paz has said, “The study of this site will change forever what we know about the emergence [and] rise of urbanization in the land of Israel and in the whole region,” and “… it means that what we know now will change what is written today in the traditional books when people read about the archaeology of Israel.”

As a final example, recall how in the article on evidence or the emergence of the ancient kingdom of Edom, the researchers were able to finally prove the flourishing of an ancient Edomite kingdom consistent with the biblical account. This happened based on a new sophisticated analysis of metallurgic slag discarded from ancient Edomite copper mining operations.

The researchers stated, “While the biblical narrative describes an early, pre-10th century kingdom … the archaeological record has been subjected to conflicting interpretations, even after the publication of the new chronology that clearly demonstrates the flourishing of the region during the 12th–11th centuries. Here, the striking synchronous agreement between the technology in Timna and Faynan, evident as early as the 11th century BCE … suggests that an overarching political body existed in the region already at this time.”

In other words, thanks to a team of researchers who looked at the relevant sites with fresh eyes and new goals, the biblical account pertaining to ancient Edom was soundly corroborated. The corroboration of the biblical record has happened time and time again over the course of 2019.

Conclusion

In the first example above, it took a second team, a different set of presuppositions, and a fresh analysis of the findings to make sense of the evidence. In the second example, the discovery happened completely by accident, because no one was looking. When it occurred, though, the result was a paradigm shift and advancement in understanding of the emergence and urbanization not only of Israel, but the whole region.

Finally, in the third example, researchers with a very specific set of goals were able to interpret evidence in a new way allowing them to piece together a more complete picture of ancient Edom. That new picture fits with a very old description, a description of Edom found as early as Genesis 36.

As noted by Scott Stripling, “The Bible and other ancient religious texts is what has driven archeology in this region.” Further, he stated, “We have to recognize the validity of the Bible… I am comfortable with the biblical story – and now we have proof of that story, really.”

These realities are exciting because they challenge traditional thinking, overturn paradigms, and introduce new perspectives. Most of all, we are watching the advancement of Scripture as an objective source of reliable history. In the next installment, we will look at some of the tools that readers can utilize to expose poor thinking. This is thinking characterized by prejudicial conjecture, unargued philosophical bias, logical fallacy, incoherence in thought, and more. At different times, we have all been guilty of these errors. Refining our own critical thinking skills is definitely an exercising that will keep us Thinking!

The post Biblical Paradigms Amongst Scholars appeared first on Patterns of Evidence.

See all posts in Biblical Archaeology News & Opinion

Upcoming Tours

We would love to walk with you in the Holy Land. Here are upcoming opportunities:

Jun 27 — Jul 09, 2024 Egypt & Jordan Walking Tour (easy pace)Led by George DeJong |

All trip dates subject to change.